#TBT - Grassroots Distribution: Growing (Cam)Pains

John Tintori

Last week we talked about trusting your communities - from production crews, to PR staff, to local supporters, and beyond - to help bring your film to the world. It's a Snowflake Model of film marketing and distribution.

In order to make that strategy effective, you need to know your film's message, boundaries, and opportunities. You need to define a campaign.

Josh and Michael identified 3 kinds of campaigns that filmmakers can apply to their film's marketing and distribution plans:

- Film that is its own campaign

- Film for social action

- Film as social action

FILM THAT IS ITS OWN CAMPAIGN.

The surmountable challenge to organize around is the film’s presence and life in the public consciousness and the larger marketplace. This is what volunteers and organizers would advocate for, and the agenda they would be pushing at every step. This seems the purest form of campaign and best use of organizing tactics; if one is to use grassroots organizing in film, it stands to reason it should be to solve the problem of birthing and supporting a film’s life in the world of an audience, with no other goal.

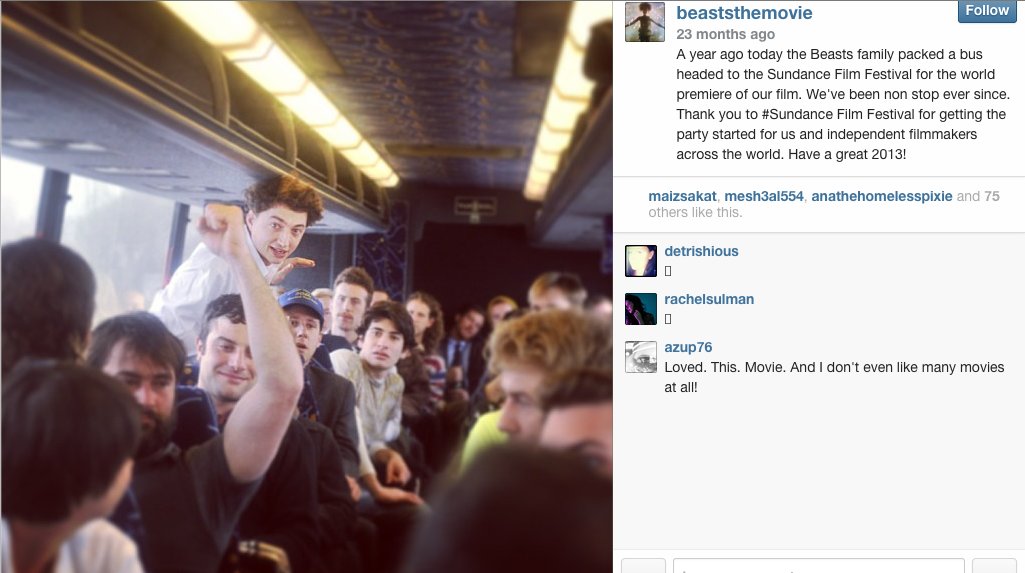

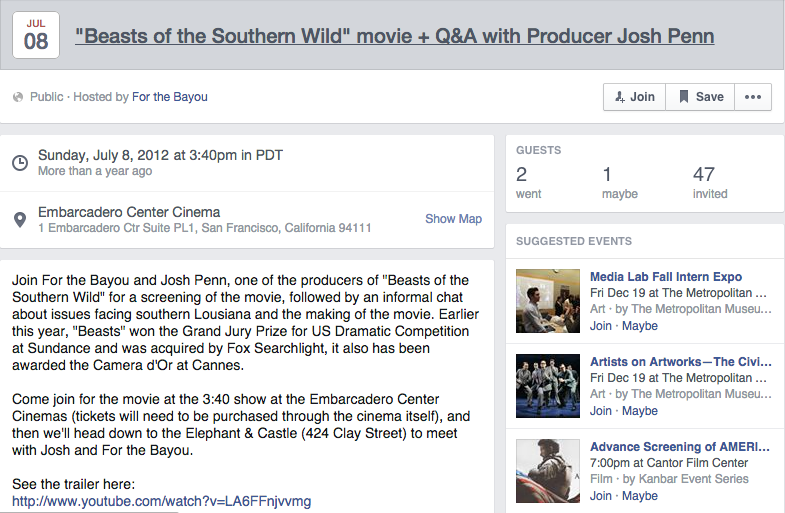

What we did with Beasts of the Southern Wild, to complement Fox’s mega marketing machine, would fall in this category. We mobilized members of our crew to go to Q & A’s in regional theaters, as a draw to get audiences to come out, and deepen the connection they had with the film, which could then be transferred into their own advocacy (snowflake model!). The thing we were up against, we would say, was the marketplace itself and the very tiny room that Hollywood’s relationship with exhibitors allows for a small independent film like Beasts. We managed the message of our online presence in complementary ways.

FILM FOR SOCIAL ACTION

In this paradigm, the film—though its own work in and of itself—is being used as a political

tool to accomplish other action. It is, in other words, part of an organizer’s arsenal—a

way of bringing people into something larger. One film we studied was Speaking in

Tongues, which deals with issues of secondary languages in schools. Their campaign

attempted to raise awareness of the importance of bilingualism through community

screenings, educational distribution, and community action. In other words, they

explicitly imagined and positioned their film as a tool for social change

There are upsides and downsides to the film’s potential life as a film that being subsumed

to a larger cause comes with. The assumed downside is that grassroots energy is going

somewhere other than to the film’s success itself. In perhaps too ideal a world, a film

would be worth supporting just as a film – or perhaps that is too cynical a world, in which

films can’t stand up on their own artistic merits. Narrative films, especially, can endow

audiences with real affection because they can come at a fictional world with more of

their own projected meaning and significance. But especially in the documentary space,

films have been a successful organizing tool for a very long time. Also, social issue films

(of which there are more documentaries than fiction films) inherently have a sense of

urgency and refer to topical things that lend themselves to a campaign-like structure: this is a problem and we need to mount an effort to solve it.

This campaign-like structure also lends itself to a real difference in fiscal support. Of the film projects successfully supported on Kickstarter, 80% are social issue documentaries; filmmakers benefit from the sense on the funder’s part that they are contributing to both a cause and a film.

Finally, another upside of films with external action campaigns is that they do achieve something inherently measurable. You can measure what impact a film had – for example, the BritDoc Impact Reports for the nominees of their PUMA BritDoc Awards. The producers of The Visitor know that their efforts trained 2500 immigration lawyers, who helped 10,000 detainees (read more here).

In a world where the perception of a film’s success is muddled by distributors who want nothing less than to tell you how a film really performed, these metrics mean something. They say: this film did something.

An article we studied compared two different films, one from each of these different

categories, to illustrate this point: We Were Here, a documentary about HIV awareness,

and a romantic comedy titled Henry’s Crime. Although both films apply similar

grassroots methods by reaching out to core constituency groups to help promote the

film, We Were Here had a much more successful distribution run. The issue of HIV

awareness generated a sense of urgency that motivated supporters and advocacy groups

to spread the message of the film. In contrast, even though Henry’s Crime tried similar

grassroots tactics like reaching out to the fans of stars in the movie to help promote, there was less urgency surrounding the romantic comedy, and the film flopped (more here).

FILM AS SOCIAL ACTION

The sweet spot—the place where the aims of politics and film meet perfectly for a

grassroots film campaign – is a film that achieves its external political action goals by

showing the film. The recent example is The Act of Killing, where the political act of the

film was to show it in as many places as possible in Indonesia. Here the success of the

film as a tool and as a film are one and the same. (Then there are some who dress up a

film that just wants to succeed in the prestige circles or the marketplace as if it has higher ambitions. See: Harvey Weinstein framing Silver Lining Playbook as a catalyst for

discussion about mental illness. See also: our eyes rolling).

What's key here is information sharing: if you know what your film means to your audience, you can use existing campaign models to do some of the strategy work for you. There are case studies out there - lots on Josh and Michael's blog here on the CRI site - that can help you get your film to the right audiences better, faster, stronger.

Talk back! Share your film campaign story and we'll highlight it in an upcoming post here or on Facebook!