If you have ever broken up with someone, only to hear from friends that you got dumped, then you know how unreliable the witnesses to history are.

Conventions used in films to tell tidy, linear stories about the past have bothered me for about as long as I can remember. For many years I’ve wondered about ways that filmmakers could signal to audiences about the unsteady platform we teeter upon when we endeavor to show what happened before. There has to be a way to foreground the present in the past without completely abandoning narrative, since I agree with Robert McKee, it is the way most of us make sense of pretty much everything.

In the 1970s historiography exploded with critiques of the way that historians present the past. That was a while ago now and yet those conversations have not really penetrated the film world where filmmakers continue to construct historical narratives in ways that historians would label as so very nineteenth century. This puts filmmakers, embarrassingly, a couple centuries behind… or at least pre-Altamont (1969), stuck in the past they seek to re-present.

Thanks to the very good people at the Cinema Research Institute at NYU I have the privilege to blog for the CRI about my project this year, which aims to do the following:

1. Consider ideas about history from historians that could inform filmmakers’ creative choices

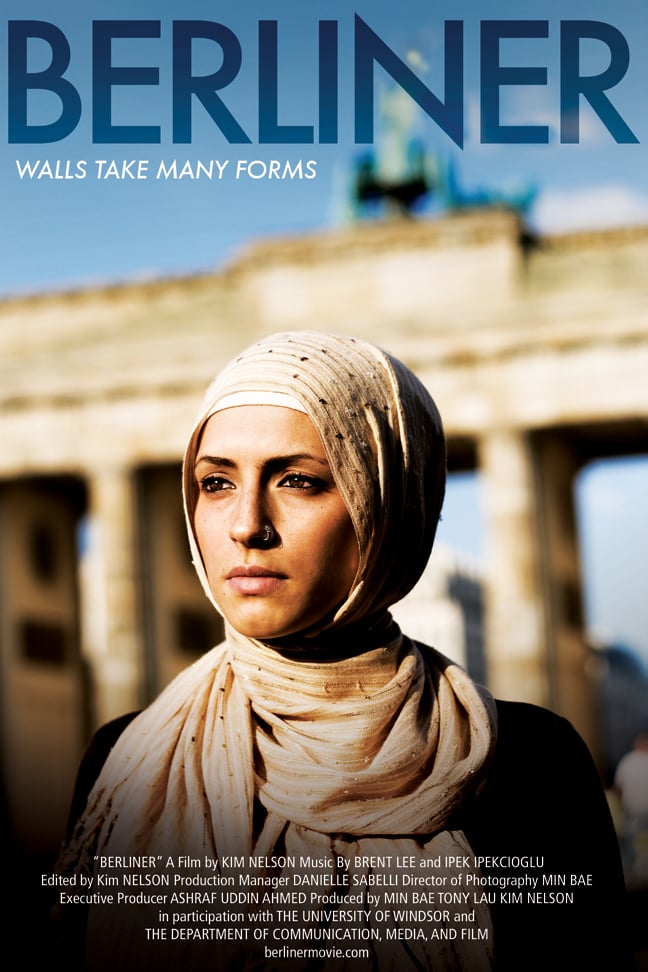

2. Explain my process of making a documentary about history that seeks to deconstruct some of the conventions of audiovisual history

3. Create a live interactive experience from the raw materials of my documentary

4. Take interactive ideas from the digital space and put them into the live performance space

5. Explore Live Documentary as a way to create unique cinema experiences

I will explore the following questions:

1. How can we use cinematic language to express different historical interpretations?

2. Can we reflect postmodern perspectives without alienating almost everyone?

3. Can new expressions of film online be reincorporated into the live environment?

4. How can filmmakers tell the “truth” about the past?

5. Is live cinema a viable way for independent filmmakers to reach new audiences?

6. Can we reengage film audiences in theatre spaces in new ways?

I will blog weekly focusing on the following topics:

Process – explaining my progress in making a film that engages history theory and transforming that film into a live documentary performance.

Ideas – exploring ideas from history as they pertain to storytelling, and the film world as they pertain to history.

Innovators – Monthly features about innovators in the fields of history, film and live audiovisual performance.

You can check out my websites here:

documistory.com

thekimnelson.com

Thanks for reading and hope you will be back to check out my blog next Monday.