Archive

Filtering by Category: Crowdfunding Platforms

What's in it For Me?

Claire Harlam

I recently posted about this article on gift logic (vs free market logic), a social means of relating that governs certain cultures (like the Tiv of West Africa) and makes certain online platforms (like Kickstarter) work. Then someone seriously revamped our CRI website and accidentally killed that post in the process. So I just wanted to re-post the link to this compelling article since the author articulates relevant points about transactions that strengthen relationships, platforms that build communities, and social mechanisms that fund art. My CRI project is ultimately focused on understanding how online tools could support such transactions, platforms and social mechanisms, so I really appreciated this thoughtful perspective. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/10/magazine/why-would-you-ever-give-money-through-kickstarter.html?pagewanted=all

Community vs. Blob

Claire Harlam

I've written plenty here about innovative and exciting platforms for independent film distribution and/or discovery (plenty enough to make at least myself and probably you repulsed by the words Innovative, Exciting, Platform, Distribution, And/Or, and/or Discovery). I've also written a lot here about how few of these platforms actually deliver on their promises to connect filmmakers and fans. My CRI project is about this connection, about community--defining it, understanding why it is a critical component of the online ecosystem for filmmakers, and studying the attempts that startups and institutions have made to build and address it. Community is critical because if it isn't there, than it really doesn't matter if your film is. Is a good library enough to draw community? Recognizable and trustworthy curators? Interaction? Involvement? Empowerment? I think it's some kind of combination of all of the above, with an emphasis on everything that came after "good library." Which is not to say that the quality of content doesn't matter in the online ecosystem. Of course it does. And there are enough quality films not getting (or not getting enough out of) traditional, theatrical distribution to populate a robust online ecosystem. Rather, online communities want an ontologically online experience--they want a unique kind of empowering involvement that does not exist in an offline world. And so some excited rambling about two organizations (a bootstrap startup and a leading institute) that are tackling the community question in truly Innovative And/Or Exciting ways:

One of the platforms I've been researching that I think is killing it is Seed&Spark, (whose COO (and my Tisch classmate) Liam Brady is using the platform to seed and spark his film, FOG CITY). Emily Best, founder and CEO of the company, writes that she "founded Seed&Spark to allow indie filmmakers to leverage this WishList crowd-funding method specifically to build and grow their collaboration with their audiences for the entire life-cycle of a film," because "...when you activate the imaginations of your broader community, you set off a chain of actions, reactions and connections the result of which can push the boundaries of your film beyond what you imagined." The "WishList" to which she refers is essentially a wedding registry for an independent film. Best first experimented with the WishList idea for her film LIKE THE WATER:

What we came to call the "WishList" rendered our filmmaking process transparent to our community and sparked their imaginations. They started coming up with ways to get involved we hadn't imagined. They became deeply meaningful collaborators in the film who then lined up – literally – around the block to see the film when it was finished. ... When both you and your supporter can name the material contribution they made to your film, you both understand your supporter’s importance beyond the number of dollars they contributed. And they should feel important because they are.

Best understands that a community needs to be empowered and thus feel important in order to thrive. So many brands spend so many corporate dollars trying to create online communities and make them feel important. But this is a difficult verging on deceptive task since the individuals who comprise these "communities" are ultimately as important as any other individuals from like demographics. For an independent film, however, individual supporters are actually important because they can, as Best points out and as Seed&Spark allows, contribute uniquely to that film's actualization. I have $50 to donate, you have a car to rent cheaply, he has c-stands to lend, etc. It's kind of beautiful how the needs of an independent film and its online community align like this. All independent films depend to some degree on the good will of communities--local communities, friends, family and peers of the filmmaking team, etc. And a community by definition thrives on supporting its members (that's why it's a community and not a nebulous blob of loners). Seed&Park offers online tools to facilitate this good will and thus connect filmmakers and fans in a profound and uniquely online way.

The Sundance Institute has announced that its Artist Services program will expand its suite of digital tools through partnerships with Tugg, Vimeo, Reelhouse, and VHX. These partners join Kickstarter, GoWatchIt, TopSpin Media, as well as the usual retailer suspects. The above hyperlinked IFP release as well as this IndieWire article provide information on these platforms, and I've also written about several of them on this blog. Artist Services is further partnering with other organizations which will select filmmakers to share Artist Services privileges with Sundance alumni. The organizations are: The Bertha Foundation, BRITDOC, Cinereach, Film Independent, the Independent Filmmaker Project and the San Francisco Film Society.

It is clear that the Sundance Institute is committed through Artist Services to exploring the community component of the online independent filmmaking ecosystem. Between their retail partners (iTunes, Hulu, Netflix etc.), and the partner platforms that help filmmakers strategize their direct-to-fan distribution and marketing (TopSpin, VHX, Reelhouse), #AS is providing their filmmakers a pretty robust toolkit for self-distribution. By additionally partnering with platforms like Tugg and Vimeo, #AS is acknowledging that an engaged community is as important as quality marketing or visible shelf-space. Tugg directly involves and thus empowers its community to bring the films they want to see to their local theater. Despite their nascent experiments with monetization, Vimeo is essentially a community of people who make videos and people who watch them. Although YouTube's community is bigger (like hundreds of millions bigger), Vimeo's superior user-interface/experience, profile customization, and opportunities for discovery (staff picks, categories, etc.) make it feel like a prettier, comfier, more tight-knit community. (There are other differences, of course.) However it stacks up against its opponent, Vimeo is indisputably a community, not a tool for direct to fan strategizing. Artist Services does not end its suite of tools at direct to fan strategizing platforms because tools that empower communities are as vital to a film's self-distributed success.

I'd like to believe that we are in fact being wired together, not apart, but I also think that there's space and time for both the movies we watch together in theaters and the ones we watch alone on personal screens (as long as they're at least 13 inches or so). Personal feelings about the anthropological impacts of online connection aside, the independent filmmaking and loving community is very real and very capable of helping each other make and discover movies online. To me, online community means a collection of real individuals that make real things happen via the Internets (online communities fund films; online nebulous blobs produce analytics). To different platforms, community means different things. Some don't need it (Netflix) and others can't live without it (anything I've written about here). I'm interested in online tools that by virtue of being online tools help a widespread group of like-minded people come together and Seed, Spark, Kickstart, Gathr, and Tugg stuff--tools that empower our community.

New Year's Resolutions & CRI Solutions

Claire Harlam

In the first week of the new year, most blogs and papers have published articles on new year's resolutions for the film industry and/or wrap-ups of last year's highlights and statistics. Some of The Wrap's resolutions are particularly relevant to the work that CRI fellows are doing now.

Some highlights and areas for consideration:

CHRIS MCGURK, CEO, Cinedigm: People have to re-screw their heads on about the way a film is released. It used to be that a movie had to be picked up by an independent distributor and get to 500 screens to be validated as a movie, but it takes $5 million to $10 million in marketing to do that, and it makes it difficult to get a return on your investment.

The way that a film can be released is an interesting consideration now from micro to ultratoobig budget projects. Ryan has designed his project to "address the lack of economic transparency in independent film with the ultimate goal of helping filmmakers better understand the options available to them when it comes to distributing their films." With a better understanding of the real costs involved in distribution, independent filmmakers will have a much easier time re-screwing their heads on in order to embrace changing release strategies.

FRANKLIN LEONARD, Founder, the Black List: I spend a lot of time thinking about data and how data can be used to improve the film business. One way that seems both obvious and interesting is making movies that already have an audience. Hollywood typically assumes that means, "Oh there’s a built-in audience for this board game." That’s wrong. It means determining ways to identify audiences for specific subjects or ideas via the internet, social media and surveys.

I agree with Leonard--the film industry has barely begun to collaborate with and learn from the tech world in order to harness data about what audiences want. Which is not to suggest that filmmakers should start making movies based on what audiences want. (That would be a cynical verging on gross thing to suggest.) Better tools to target individuals based on their interests and tastes mean better chances for filmmakers and grassroots distributers to build audiences around any film. I'm researching new digital platforms in this space, I'm trying to understand how to build community around film online and learn from that community, and I'm (hopefully) killing the word niche in the process.

GLEN BASNER, CEO, FilmNation: ...It’s much easier to have a hand in the creative process and in the development of a movie than when you're getting a big fee from the studios, making $20 million before you step on set. Don’t get me wrong, studios have a lot of strengths -- more advantages than disadvantages -- but they are not nimble. They can’t tailor each project to specific filmmakers. That has allowed smaller companies to enter the void and have a bigger impact than ever before.

Edward is aiming with his project to build "a new model of independent filmmaking focused on the production of feature films produced within the walls of the university system that will prove to make dollars and sense." Like Basner suggests, now is a perfect time for filmmakers working within a nimbler infrastructure than the studio system to "enter the void." And no one but no one is nimbler than a film student.

Full article here: http://www.thewrap.com/movies/article/how-improve-hollywood-9-experts-weigh-future-film-70126?page=0,0

Getting Personal

Claire Harlam

"Users tell us they don't know what to listen to, and artists tell us they want to connect more closely with fans" says Daniel Ek, CEO and founder at Spotify. "So we're creating a new and personalised way of finding great music."

Spotify recently introduced a suite of new functions as part of their mission to make music discovery more personal. There are very many, very obvious differences between film and music, differences that make music far more apposite to the constant (social) consumption that Spotify encourages. Still, I think that the creators of online platforms for filmmakers and filmfans should study Spotify and its recently added tools (or at least watch this precious little thang).

The new tools for getting personal are "discover" and "follow" tabs that, in essence, allow Spotify users to curate their curation by choosing which artists', influencers' and friends' recommendations to follow. Unlike platforms I've written about here which do not clearly explain how they will deliver on their promise of filmmaker-fan connection, Spotify recognizes that curation is a key step towards both this connection and towards discovery of new content. As a musician, my connection to a fan is strengthened when he chooses me as a curatorial guide. As a fan, who better to introduce me to new music than the musician who knows that world (and my taste, by virtue of my choosing him) best? By fostering this unique kind of regular interaction between fan and artist, Spotify is both strengthening fan loyalty (for whenever the artist may need it) AND creating a mechanism for discovery.

"From today, music discovery becomes truly personal. It becomes central to the Spotify experience as the service brings artists and fans closer together than ever before."

Yes, music and movies require different modes of consumption and cannot be considered similar for the sake of a business model. But many platforms that are trying to make film discovery truly personal should note how Spotify is marrying personalization with artist-fan connection. Discovery is possible without curation thanks to sophisticated algorithms. But there's nothing personal for artist or fan about connecting with ones and zeroes...

Read more about Spotify's new tools here.

How BitTorrent Will Help Artists

Claire Harlam

"The email address is the most valuable thing you can get from a consumer. It's probably worth more than a direct sale through iTunes," according to [Matt] Mason, who says the artist can then use that email to sell the fan multiple albums, concert tickets, merchandise and more down the line. We [BitTorrent] did a campaign with the author Tim Ferris on his new book "The 4-Hour Chef." In the first seven days of that campaign, we saw 210,000 downloads of the sample of the book. That's awesome, but what's even more awesome is that of those people, 85,000 of them then visited Tim's Amazon page for the book. That's a sick conversion rate. That's off the charts.

BitTorrent, the file sharing protocol, moves 30% of Internet traffic. BitTorrent, the company, is dedicated to figuring out how they can help content creators take advantage of this staggering statistic.

Here are some highlights from an interesting and encouraging MediaShift interview with BitTorrent's director of Marketing, Matt Mason:

When it comes to entertainment companies, they have an in-grown fear of piracy. Is it hard to change their minds so you can work with them?

Mason: Yes, absolutely, and it's difficult to convince people, and convince everybody at a company that it's a good idea [to work with us]. We might convince a band, their manager and the CEO of the label, but the [general manager] of the label might say, 'You can't work with BitTorrent ever, ever, ever. It means piracy.' And we don't ever get to talk to that person. It's difficult, but we are seeing the tide turn. Over the last year, we've done a lot of cool stuff with content. And when we go out and talk at media events, we tend to get a different reception; people are interested in the experiments we've been running.

Moving into 2013, our mission is: How do we create as many great tools for publishers to access the BitTorrent ecosystem as there are for consumers?

Have you tried getting people to pay for downloads?

Mason: We've experimented with having people pay right off the bat, or at least allow people to donate. Last year we did a really interesting experiment with a TV show called "Pioneer One." Two filmmakers from New York made a pilot. The pilot got a lot of attention and won an award at Tribeca. They were interested in a new way to distribute it, and even a new way to fund the production.

Funding TV is kind of crazy if you do something with one of the big networks or cable channels. You might get $4 million to make your pilot, and it could be great, and it could get great feedback in focus groups. But if there's a scheduling conflict with "Desperate Housewives," that pilot could be shelved and no one will ever see it. That's a reality for a lot of TV producers.

These guys were interested in creating a show and finding out if people were actually interested in seeing it. We put up the pilot through BitTorrent for free, and we gave people the opportunity to donate to make Episode 2. They had between 4 million and 6 million downloads of Episode 1 and got enough donations to make Episode 2. Then they had enough donations to make Episode 3, and then 4, and so on. They got enough donations to make an entire season of "Pioneer One" that ran over an entire year. That was a successful experiment, which was funded directly by the BitTorrent audience.

That's one thing we did, but we've done many more. Our take is that there isn't any one way to distribute content in the digital world. There's actually a different business model for every piece of content.

paywalls and tipjars and ads, oh my!

Claire Harlam

For many reasons, I'm excited about the new Made in NY Media Center, a pioneering institute run by the Mayor's Office of Media Entertainment in partnership with IFP and General Assembly that will give a home and various support to the many people studying or working within the fertile and freewheeling space where the entertainment, technology and advertising industries meet. Central among my reasons for excitement is their "Digital Advertising Academy," "a think tank [that will] help solve real-world brand marketing challenges." The deeper I get into my CRI research project, the more strongly I feel like innovative digital advertising is one of the more critical missing pieces in the online-content-revenue-generation-puzzle. Experiments in digital distribution run rampant, but their innovations lie mostly in streamlining technological processes to get films online and into key distribution channels or in using crowd-sourcing to revise traditional models of financing and exhibition. I've written already about how many of these new platforms fail to actually bring filmmakers and audiences together, despite some of their claims to, and how important this social element is to both the creation of a successful "online community" and to a filmmakers' ability to identify his audience ("niche" or not). I haven't yet explored one economic apparatus that could potentially sustain such an "online community"--innovative advertising.

Mr. Urlakis, commenting for an article on sproutsocial.com titled "How to Monetize Your Youtube Channel," references a decision he made to not take advantage of YouTube's Partner Program. Some lucky generators of content ("filmmakers?" "artists?" whatever) have managed to make a living and then some through the Partner program. Still, Urlakis makes the important point that he could alienate potential fans by running the ads he needs to earn an income.

Vimeo's platform has since its inception been an antidote of sorts to YouTube, a place where artists less concerned with virality than quality feel comfortable sending people to watch their work. It would make sense that they have taken a different approach to content monetization.

To help their users make income and thus be able to "create more great work," Vimeo introduced to their site "tip jar" and VOD services. The tip jar allows for seamless deposits into the filmmaker's PayPal account, and the VOD service, to be launched in early 2013, acts as a typical paywall with pricing set by the filmmaker. The tip jar service invokes the interesting "Pay What You Want" behavioral context, which is appropriate since it allows people to feel like they're doing a good thing by paying for content, which is (let's be real) the impulse behind the financing of most truly independent films. Vimeo's tip jar is very young, and its VOD service has yet to launch, so little information exists on whether/how much artists have benefited from these services. Inevitably, there will be some success stories. Still, one service is fundamentally based in old guard economics (pay for content), and the other is, simply, charity.

Vimeo and Youtube are both obviously paramount platforms for generators of content and filmmakers alike, and they should be commended for offering their users opportunities to make income from their work--especially if, as Vimeo CEO Dae Mellencamp suggests for her company, there is no revenue in it for them. It's still worth noting that paywalls, tipjars and (traditional) ads are familiar features of pre-digital distribution, and it's worth wondering what's next.

Filmmakers should be able to find their fans online. Fans should be able to discover films online (whether they comprise a target audience or not). Perhaps a platform has not been able to make this happen sustainably for itself and for its filmmakers because advertising has not entered the equation in an innovative way. What kind of advertising would fans of quality content be not just willing but happy to sit through? Maybe this kind of advertising wouldn't require sitting through but interacting with. How could such interaction be incorporated authentically into a social context? These questions are vague, but a response has been defined by the Made in NY Media Center: innovators from the filmmaking, advertising and technology worlds will come together as a think tank to address the challenges facing producers, startups, and brands alike. This cross-industry collaboration is a pioneering innovation itself, and one that will be so exciting to follow!

Indiewire Readers Wanted and Desired -- For Film Independent's First-Ever Movie Hackathon!!

Claire Harlam

I'm so excited to see what comes out of this...

Helping One Another Become More Intense

Claire Harlam

Is the use of the phrase virtual community a perversion of the notion of community? What do we mean by community, anyway? What should we know about the history of technological transformation of community? Is the virtualization of human relationships unhealthy? Are virtual communities simulacra for authentic community, in an age where everything is commodified? Is online social behavior addictive? Most important, are hopes for a revitalization of the democratic public sphere dangerously naïve? --Howard Rheingold, The Virual Community (325)

Media theorist and widely agreed upon coiner of the designation "virtual community" Howard Rheingold asked these critical questions as he watched OG social-networking blow up in 1993. Nearly two decades later, these questions remain understandably unanswered--they're tough! But while it's understandable that theorists grapple still with these questions, it's unsettling that members of the "communities" in question don't seem to have interest in the implications of such questions. And if it's unsettling that "community" members don't seem to have interest in the questions, it's foolish that founders of such professed "communities" don't address them at all.

Rheingold continues (338):

Ethical issues occurred to me when I entered the business of growing virtual communities. Is building a virtual community for parents, for example, using money provided by a company that sells diapers, a way of turning community into a commodity? Is this a bad thing? Is it really right to call a collection of web pages or smutty chatrooms a “community?” how much commercial ownership are the members of a virtual community willing to accept, in exchange for the technical and social resources necessary for maintaining the community? Is it possible to be in the business of building communities for profit and still write about them?

"Ethical issues" can be understood as "market risks" here if it makes the business planner comfier--the point is that Rheingold considers how actual members of a community will respond to the predetermined virtual ecosystem built for them (if also for investors).

Author-composer-scientist-legitimate multi-hyphenate Jaron Lanier writes in his You Are Not A Gadget (47):

The 'wisdom of crowds' effect should be thought of as a tool. The value of a tool is its usefulness in accomplishing a task. The point should never be the glorification of the tool. Unfortunately, simplistic free market ideologues and noospherians tend to reinforce one another's unjustified sentimentalities about their chosen tools.

Many among the small coterie of folks who write about and/or experiment within the online world of film distribution and discovery assert the importance of "new" and "sustainable" "tools" and "models." Few, however, consider who exactly will use these tools, how they will use them, how they will know about them, and what tasks the tools will ultimately accomplish. There are some fantastic new online tools for filmmakers, like that offered by website Kinonation (the start-up evolution of which Roger Jackson has been so generously and transparently blogging about on Hope For Film) which accomplishes the critical task of allowing filmmakers to upload their work in order to have it transcoded to the different formats required by various VOD and EST services.

KinoNation further aims to help their filmmakers find an audience. It remains unclear to me how tools that allow selected filmmakers to get their films online (other examples include: Sokap and Yekra and even VHX For Artists for artists who aren't Aziz Ansari) but which don't have built-in audiences (like YouTube channels or Kickstarter) plan to connect filmmakers and fans. These platforms rightfully assume and assert that there are legions of potential fans out there consuming an unprecedented amount of content, but they don't explain why these legions will assume their specific tools.

Filmmaker and fan connection is a task that needs a tool, and it most likely won't be the same tool that gets a film transcoded, crowd-funded, or "liked" by the filmmaker's friends. But as soon as you're talking about the people involved (filmmakers and fans) as opposed to the technology, you're talking about social behavior and you're talking about "community." And the general questions surrounding virtual community and behavior are no better answered now than they were in 1993. I have focused my CRI research on these questions because I think their exploration is crucial for building the tool that can address the specific task of connecting filmmakers and fans.

"The places that work online always turn out to be the beloved projects of individuals, not the automated aggregations of the cloud," writes Lanier. He signals out one such place, a community of oud players (super legitimate multi-hyphenate) where "you can feel each participant's passion for the instrument, and we help one another become more intense" (71-2). (How) Can an online tool allow us to help one another become more intense, and, by assumed extension, more involved, more invested, more interested in each other's work and in each other?

Communities Run On...Transparency?

Claire Harlam

Here's a thought-provoking post by Chris Dorr on indie film and network effects (in case you didn't already see it featured on the Truly Free Film blog). Film people talk a lot about transparency these days, but they rarely consider its implications beyond making the folks at companies who require discretion with numbers vaguely uneasy.

Chris' suggests that thorough, generous transparency (like that offered by James Cooper with his kickstarterforfilmmakers project) if continuously offered and collected by an active community (still grappling with that word) has powerful potential to create a network effect. This (very) basically means that the more transparent information is offered by the participants of the network, the smarter, more powerful and more attractive the network becomes.

The obvious questions remain: what does this network look like? What are the online tools available to facilitate such a network?

In a class I took at ITP on online communities, our lovely teacher Kristen Taylor/kthread would systematically bring us back to the question "Communities run on...?" Love, passion, connection, purpose, and other such adequate-verging-on-necessary answers came up often. I don't think that transparency is a requisite community engine, but I think the implications of its employment for a network of film fans and makers are exciting and require further examination. I'm on it!

What else do (online film) communities run on?

"—to whom a particular film is relevant—"

Claire Harlam

Gathr is a self-described "love child of Netflix and Kickstarter." Its self-described core service is "critical mass ticketing." It's basically a platform for crowd-funded screenings of finished films (old and new), much like Tugg. (Here are descriptions of the two platforms in tandem--sorry, I couldn't find an actual comparison. When I get to the in depth platform analysis stage of my research, I'll try to pinpoint the respective services and company dynamics that make the two platforms distinct. All I can tell from the surface is that Tugg is farther ahead in its collection of titles and relationships with established exhibitors.) Gathr's mission is plainly dope. They are providing the tools for filmmakers to (comfortably) stop asking permission of a system that is "archaic, inefficient, top down, and completely misaligned with the interests of the vast majority of filmmakers and their investors" to get their movies seen. But they also might be overestimating how currently well-suited our internets are for a filmmaker (or his team) to promote a movie adequately enough to achieve the tipping point for a screening. More on that in a bit (a little bit more in this particular blog post and a lot more in my CRI research project).

Fanhattan is (from what I can tell--it's currently only available for the iPad that I still don't think I need for whatever ridiculous reason) a pretty sophisticated and helpful aggregator of aggregators--it's like a pimped out, user-friendly CanIStreamIt. No, it really isn't anything like CanIStreamIt except that both share the daunting goal of bringing order to the chaos of content streaming and renting/purchasing. Fanhattan integrates not only with Netflix and Hulu but HBO, TV Everywhere (Time Warner and Comcast's platform for cable customers to get exclusive online content), and most TV networks (ABC, NBC, CW, etc.).

Fanhattan is further integrated with Facebook's Open Graph, but I think their implementation of the graph seems (again: no iPad) more thoughtful than the ubiquitous and eerily reductive "like" and "comment" features on which most Open Graph integrated platforms settle. Fanhattan's implementation seems more thoughtful because it is in service of its "watchlist" function. The watchlist is a curated list of movies and tv shows (old, current, in production) that Fanhattan's users create in order to receive updates about when and where the content becomes available. Users can also share watchlists, which renders all that liking and commenting meaningful since in this context, these functions can actually lead to someone discovering something or some similar kind of serendipity. People don't want to "like" your shit; people want to talk to each other about why they like or don't like your shit. (And it's really not all that clear to anyone why a high number of "likes" is at all meaningful. Unless I'm missing something--please comment if I am.) Communities function on meaningful experience, and meaningful (online) experiences are implicitly social.

Here's an interesting article on Gathr.

From the Tribeca Future of Film blogpost on Gathr:

[Box office statistics are] a real shame, because word of mouth, online media, social networking, and traditional marketing ensure that millions of people nationwide—to whom a particular film is relevant—will have heard about a film’s theatrical release.

I like the concept of "relevance" these days as little as I like the word "niche." Enough case studies definitely exist out there which prove that if you can just tweet enough to that fervent network of neocon surf enthusiasts, you will be able to Gathr and Tugg them enough to pay your investors back. But the goal shouldn't be to (only) acknowledge the myopic few to whom your particular film is relevant, but to find the folks who care about your work because it's authentic and good (oh yeah, by the way, I'm totally assuming that your work is authentic and good. If it isn't, it has as little business being Gathr'd or Tugg'd as it does being platform released by Fox Searchlight).

Gathr and Fanhattan are completely different tools, but for either to survive as platforms or have any real value, it needs to recognize how its users (its community, perhaps--I still need to figure out what this means) want to play with its offerings and thus which tools it should offer to quietly facilitate that playtime. Fanhattan's "watchlist" is an inherently social and useful tool that may place a necessary focus on user interaction and subsequent discovery. Gathr might need to recalibrate its tools in order to service the filmmakers and fans who don't or don't care to belong to niches. Gathr's founder himself notes in the Tribeca blogpost: "After all, there are 343 cities in the U.S. with 100,000+ people, and there are more than 3,300 towns in the U.S. with 25,000+ people." That's a whole lot of people to whom tons of particular films may or may not be relevant--how can we empower them to talk, share, and figure out for themselves what they want to see?

The more I explore this question, the scarier our delimiting social networks become. But, more on that (and the Slow Web, and the fact that You Are Not a Gadget) in another post soon.

Group Watching > Solo Lurking

Claire Harlam

I just read this article on TechCrunch about new movie- (as well as future book-, app-, game-, and tv-) recommendation platform called Foundd. And now I'm here typing in this little box because Foundd has a pretty unique value add for this space, one that's intriguing enough to have me here typing in this little box now. The value add is group recommendations:

Berlin-based Foundd is a new movie recommendation service launching this week, which not only finds you movies you would like to watch, but also helps a group decide on a movie they can watch together. It’s an interesting twist on the concept of personalized recommendation engines, like those created by Netflix or Amazon, for example, which seemingly presume that watching movies is a solitary experience. While that’s sometimes true, you’re just as often watching movies with family or friends…and arguing about what to watch.

I wasn't able to actually test out this group recommending/viewing mechanism since after onboarding I found myself with zero Foundd friends [ :( ], but I'm still excited to see a platform in the recommendation/content space whose founders are trying to build into its architecture an understanding of what its community needs to function comfortably. A quick stroll through the Foundd world does not reveal beyond the group recommendation function much more of an attempt to differentiate itself from the bigger player Netflixes or smaller renegade Filmasters of this space.

Still, it's clear that the Berlinese men of Foundd are thinking about their community's needs and group behavior generally, and it will be cool to see if/how they move more towards making Foundd a real-time community experience instead of another static (if helpful) algorithmic lurk-zone.

Whoopi's Wisdom, Or Why Famous Folks Who Don't Need Them Are Turning To Crowds

Claire Harlam

In this IndieWire interview, Whoopi Goldberg explains her decision to use Kickstarter to fund "I Got Somethin To Tell You," her documentary on Moms Mabley, a black, female comedian who influenced Whoopi and many other comedians with a penchant for addressing some of the less comfy issues of their times. In discussing why she turned to the crowd, Whoopi notes:

I could have gone back to one of the cable stations, but what that means is you don't get to do the project the way you want to. This project is about the impact that Moms had on people. Impact on comics. It's less about her life story and about what she brought. She was the only female comic for about 40 years! That's never been celebrated and it's never been celebrated as a woman. She was on the cutting edge, a pioneer, talking about things that nobody was really talking about at the time and how she did it. So that's what this is about.

The sentiment here (which is similarly apparent in remarks like "[My crowd-funders] want to see good stuff and they don't mind contributing what they can," or "This isn't a little bullshitty project") is uniquely that of someone who is established and connected but still choosing to step outside of a system that can work but not without an often impeding amount of begging and meetings and opinions and begging. Whoopi, like Paul, Amanda, and Louis, simply gets it: if I can get my fans to fund what I do directly, I can do it how I want to do it, plus I can give them rewards, shield them from middle-man screwing, and other such heart-warming perks. Of course simply getting it is easier if you already have a lot of loyal fans, but one of the goals of my CRI project is to figure out how filmmakers can find the folks who love what they do--to figure out how to define community and build it. So, stay tuned.

For now, back to Whoopi and co. If you're reading this, you're undoubtedly reading lots of other writing on the disruption, the disintermediation that these established artists' decisions to turn to their fans for direct support signify. Chris Dorr, who has generously shared his expert perspective with me and helped to hone the approach and scope of my CRI project, has some really fantastic related posts like this one on Amanda Palmer and "True Fans."

I want to add an observation to this dialogue that is simple but speaks to a critical and oddly overlooked aspect of direct to fan activity: these famous folks who don't need them are turning to crowds, in part, because they (the folks) love them (the crowds) back. There is something (the something I am here trying to define) that is really refreshing about Whoopi, Amanda, and Paul's frank, gloriously unironic campaign videos, about Louis' sincere, typo-ridden emails. There are actual people poking out of the screen, people who aren't particularly polished or aware of themselves, but people aren't supposed to be this way--brands are. PEOPLE ARE NOT BRANDS. More on that in just a bit.

Whoopi emphasizes that her project isn't little and bullshitty because she knows her fans "want to see good stuff." I wonder if every filmmaker with a Kickstarter campaign really believes that (or has at least considered whether) the crowds of potential fans whom they are trying to reach wouldn't find their project little and bullshitty. This is not to say that people should make what they think their fans want them to make, but it is to say (very much so) that once an artist starts asking the crowd for something, he has an (ethical? strategic? humane?) imperative to respect and understand the people who comprise it. Whoopi wants the freedom to make what she wants, but she consistently refers back to the fact that what she wants is what the fans want (and is what Moms delivered): something edgy, discomforting, and honest--"so that's what this is about." She recognizes that in the particular story of "I Got Somethin' To Tell You," the fans want the thing that they can themselves fund, and this thing will be different from the thing that the cable station would have funded. So, that's what this is, and it's pretty special.

I think the "something" that these artists all seem to possess in their campaigning and which I'm trying to define here is an open and honest appreciation for fans, an inherent respect for the people who are into what they're ostensibly into because they're making it. The most incredible thing that the internet has done for filmmakers is that it has allowed them to actively give a shit about their fans. Crowd-funding tools, with Kickstarter at the helm, seem at this point to be the only online platforms that realize how incredible the human reality of this disintermediation is and thus build the tools into their platforms to facilitate seamless connection.

The more I read that filmmakers need to "brand" themselves and have more of a "presence" so they can be "relevant" (and other words that make me feel ill), the more I understand why so many of us are loathe to explore direct to fan options. That said, many of these options themselves seem built around the premise of branding and selling. Throughout the course of my research, I am going to look deeply at platforms and tools that are trying to support real connection and community, as well as ones that want to help filmmakers find their fans. I'll also explore what connection and community are as concepts and practices in both real reality and the digital one, so that my analysis of these platforms counts for something (and so that I feel less pretentious using both words ad nauseam in one blog post). I am happy to share my working bibliography and very happy to receive feedback--just let me know. I will post it once it's slightly less of a mess.

Thanks for reading!

VHX Announces New Platform for Independent Filmmakers

Claire Harlam

"VHX wants to be your dashboard for the entire Internet," wrote TechCrunch, and most other tech blogs more or less overtly, in describing the video discovery platform that aims to "combine the best parts of the TV experience with the best of the web." VHX stands apart from the quadrillion or so other platforms who seek to do the same in large part due to its simple user-interface which does, indeed, incorporate the best parts of the TV experience (ie watching stuff without constant distraction) and the web (networked curation aesthetically reminiscent of a Pinterest board).

VHX has announced a new service for artists and filmmakers. Few details have been publicly disclosed, but VXH founder Jamie Wilkinson shared his vision for his filmmaker distribution platform service with TechCrunch:

VHX hopes to provide an alternative, Wilkinson told me by phone, by allowing content owners to create beautiful, highly branded user experiences of their own.

“Before, the Internet was where you went if you couldn’t get a distribution deal,” Wilkinson said. But now, “creators are realizing that they no longer need the distributors to reach an audience… Creators are coming around and realizing that people are really happy to open their wallets.”

I'm excited to see how this platform develops. Though VHX's offerings are similar to that of many of the other direct distribution platforms in this over-crowded market, VHX's current user interface and design are superior, and their investor activity is promising. They stand pretty poised to allow independent filmmakers to share their work on their own terms a la Louis CK or Aziz Ansari (whose direct download was VHX-fuelled).

Read the full TechCrunch article here

IndieGoGo raises $15M from Khosla Ventures, doesn’t use Kickstarter to get it

Claire Harlam

IndieGogo has some hopeful investors in its corner, which could mean the crowd-funding platform is developing a competitive edge in its battle with Kickstarter. The IndieGogo vs. Kickstarter question is already interesting. Most filmmakers (or other campaigners) realize that IndieGogo allows them to keep whatever money they raise, unlike Kickstarter which lets no money exchange hands if the filmmaker falls short of his goal. Still, Kickstarter is the more popular platform, both in terms of projects hosted and money pledged. People are obviously spurred by the all-or-nothing mentality--spurred to donate and to promote. So, what will be IndieGogo's $15 million response?

Who knows. But I am interested by one function IndieGogo has already unveiled--their new proprietary algorithm that promotes projects based on a number of inputs having to do with their popularity and engagement (of creator and fans). People like to talk about the "democratizing" power of the internets, but it seems obvious that politics are often as much at play on platforms for online funding and distribution as at film festivals. IndieGogo's algorithm provides for some legit democratization. I'm excited to see whether they move further in this direction, though also weary of the caliber of projects given their current wholesale dearth of curation.

Article here.

I Need Your (special, engaged, aware) Mind For a Moment...

Claire Harlam

I've spent my first three months as a CRI fellow surveying the space I want to research and analyze as comprehensively as an ever-evolving field will allow, which is the strange new world where online content, community, discovery and curation meet. A critical and ongoing component of my CRI project, I will write a biweekly column that will live on various sites and systematically analyze this world (based on a rubric that I will share in my next post). Each column will focus either on a specific platform, or on a category of platforms (see list of POTENTIAL PLATFORMS FOR ANALYSIS below). I will create a malleable overview of this space that explains how any particular app or platform functions and helps (or doesn’t help) filmmakers and fans within it. Since I want to ultimately answer this research with my own platform, the column will further expose the challenges of answering a need and the barriers to entry that an every-evolving field involves.

My big problem now is that this here list is crazy long and still probably lacking some key platforms that I've either overlooked entirely because my radar is over-saturated or whose Beta test I don't know about because I'm not special enough to have received the invite.

SO, Special folks: Please leave a comment here, email me at claireharlam@gmail.com, or twittertweet @Harlam if I've left a key platform off of this list, or if you have suggestions as to how I can better focus or categorize this beast of a list.

I am trying to look at platforms that address this space (where, again, online content, community, discovery and curation meet), but I am not focusing on independent (or not so independent) film-specific platforms for the very reason that I don't think these platforms have gotten it right (and some recent Beta test suspensions would suggest that their founders would agree).

You should therefore please feel free to throw anything that interests or excites my way (anything, ultimately, that involves content and community).

There are so many interesting platforms out there right now, (almost) each with its own unique perspective and thus lesson. Help me figure out which of these lessons are going to help our filmmaking community the most.

Herein, that (beast of a) list:

(updated 6/14)

CRI POTENTIAL PLATFORMS FOR ANALYSIS

(by categories which themselves are also up for (need) debate)

DIRECT DISTRIBUTION PLATFORMS AND TOOLS

• MOPIX (direct distribution)

- “Your video app marketplace”

- A framework for content owners to quickly and easily distribute, brand and sell their content in a social-enriched marketplace via web and apps

- Users will discover, watch, experience and own content from any device they choose

• INDIEFILMZ (direct distribution for shorts)

- “Facilitating a direct and rewarding connection between the creator and audience during ‘the short phase’ of the filmmaking career”

- Direct distribution platform for short films

• VEAM (direct distribution via app)

- “Films direct to audience. Profits direct to you.”

- Filmmakers post content, filmmaker sets the price of the content, Veam creates an app for the filmmaker to distribute his content on app stores, filmmaker profits

• INDIEBLITZ

- You make films. We do the distribution dirty work. We send you money and reports. You keep making films.

- Boutique film distribution company that offers brick and mortar and retail digital distribution, and direct-to-consumer fulfillment services.

• DISTRIFY

- “Distrify turns film sharing into sales and your fans into a community”

- It’s a video-playing tool that allows whomever watches your film to buy or share it immediately from within the video player

• DYNAMO

- “Powering Independence” “Because good content is worth paying for”

- Video playing platform that can be embedded anywhere and has a seamless payment process through PayPal or Amazon.

• EGG UP

- “Sell Films Securely”

- You've put blood, sweat, tears and lots of money into your film. Now it's time to bring it to the world. Eggup provides a secured platform to help you promote your film, connect with fans, and build a business.

• DISTRIBBER

- “Your film in profit, fast”

- Pay for seamless distribution to major online digital marketplaces and Cable VOD

• SNAG FILMS

- “SnagFilms.com offers the broadest collection of great independent movies you can watch right now, on demand, for free, and share with others – films that entertain and inform, engage and inspire, satisfy every taste, encourage discovery and create community.”

• FILM BUFF

- For Filmmakers: We act as both asset and advocate to our filmmakers, partnering with them to capture an audience for their creative work. Provocative, distinct and fresh content is our focus.

- For Audience: FilmBuff pushes the boundaries of digital distribution to provide audiences with the widest possible range of viewing options. We work to provide the online content consumers demand to all possible devices on which they could choose to view it.

STREAMING SERVICES (CURATORIAL, SOCIAL, DISCOVERY)

• PRESCREEN (curated, social, discovery, VOD) **SUSPENDED***

- “Discovery one new movie each day, stream on demand”

- Filmmakers submit films, prescreen features streaming for a low price, users get an email promoting one film every day

• CONSTELLATION (curated, social, discovery online theater)

- “Constellation is your online movie theater”

- Users purchase tickets to attend schedule showtimes, or create their own showtimes for social viewing (VIP hosts, friends, etc.)

- Unclear how/if filmmakers can submit

• MUBI (curated, social, discovery)

- “Your online cinema. Anytime. Anywhere.”

- An online movie theater where you watch, discovery, and discuss auteur cinema.

• FANDOR

- “Essential Films, instantly.”

- VOD streaming service for independent, international film for monthly fee.

• OPEN FILM

- “Where creativity meets opportunity”

- Openfilm showcases a fast growing collection of high quality, live action and animated films displayed in the highest quality available on the web. Our site provides a venue for users to watch premium content and for filmmakers to exhibit their works.

SOCIAL CONTENT DISCOVERY/AGGREGATION:

• VHX (social content discovery/aggregation)

- “We’ve combined the best parts of TV with the best parts of the web.”

- Users discover video through their social network—like Pinterest, but for video content

• CHILL (social content discovery/aggregator)

- “Discover the best videos in the world”

- Users discover video through their social network—like Pinterest, but for video content

• SQURL (content discovery/aggregation)

- “The best place to watch and discovery video”

- Users can aggregate favorite videos from the web and discover new videos from their featured content

CROWD-SOURCED EXHIBITION:

• TUGG (crowd-sourced exhibition)

- “Bring the Movies YOU Want to your Local Theater”

- Users create film events, spread the word, get enough RSVPS to watch the film together

- Has a library

• GATHR (crowd-sourced exhibition)

- “Theatrical On Demand”

- Users “Gathrit” (a button by films with limited distribution), spread the word, get enough RSVPs to watch the film together

- Has a library

• OPEN INDIE (crowd-source exhibition/discovery)

- “Theatrical distribution platform for independent film”

- Filmmakers add their films, fans discover new films and request local screenings. Next they hope to turn audience demand into screenings by digitally delivering films to venues.

- Depends more on independent filmmakers submitting their films than on an existing library/licensing rights

CROWD-FUNDING

• KICKSTARTER

• INDIEGOGO

OTHER CROWD-SOURCED ACTIVITY:

• SOKAP (crowd-sourced investing/audience-engagement)

- “A network of funding, marketing and distribution of big ideas in Entertainment”

- Filmmakers license territories to users in a tipping point crowd-sourced investment model

- “Engaged” users have more access to rewards and benefits related to the content with which they are engaged

• JUNTOBOX FILMS (crowd-sourced studio)

- “created to share, develop, and make films”

- allows filmmakers to upload projects they want to develop/finance/distribute; allows fans to track projects they are interested in

AGGREGATORS/TECH. BASED RECOMMENDATION:

• NANOCROWD (locator/tech. based recommendation)

- “we know WHY people like things”

- uses a technology called Reaction Mapping® to figure out what you like, and then it tells you where that content is available for streaming or purchase

- basically canistreamit but with tech-based curation/recommendation

• FILMASTER (locator/tech. based recommendation)

- “your movie guide”

- Recommends what you should watch tonight in theaters, on TV, or Netflix based on your unique taste

• SCENE CHAT (social video sharing (and tracking) system)

- “socially ignite the videos on your website”

- allows advertisers or content creators to add a social utility to their videos—social is actually overlain within the video, so that comments can be left in real time

• WATCH IT (locator)

- “one queue, any platform”

- it’s a guide to what’s playing and where it’s playing, so that you can build a queue of movies you want to see, discover where they are playing online, share that with your friends

BIG PLAYERS (each gets its own analysis?)

(• MILYONI (Facebook fan monetizer)

- “The leader in social entertainment”

- They help entertainment and lifestyle companies convert Facebook fans into customers through their “Social Cinema” and “Social Live” platforms.

• CINECLIQ (Facebook based film-on-demand platform)

- “Turn Facebook into Your Home Theater”

- Rent films in an online Facebook-based theater)

• YOUTUBE

• VIMEO

• TUMBLR

THIRD-PARTY ANALYTICS AND SUPPORT

• ASSEMBLE

- “Build the perfect web-presence to gather your film’s audience and sell direct”

- “Clever software” that creates and manages your web-presence, gathers and tracks your audience, provides sales mechanisms to sell your film and products. Helps build your presence across many platforms.

• OOYALA

- “Powering personalized video experiences across all screens”

- Video analytics platform that tracks viewer engagement in real time across all devices for big companies. They believe the future of media is leveraging these crucial insights to create deeply personalized vieweing experiences that increase viewership and grow revenue.

CASE-STUDIES THAT ARE NOT FILM-SPECIFIC BUT DOING SOMETHING RIGHT:

• SPOTIFY

• COWBIRD

THANKS!

Claire

"Torso" Consumption?

Claire Harlam

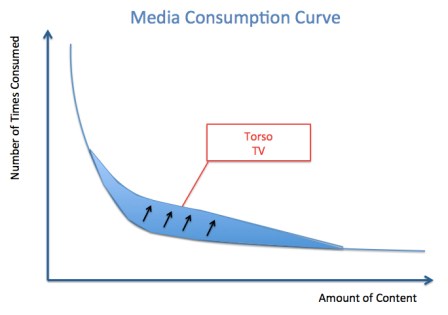

Will head end hit and long tail niche content producers battle to reap the audiences and revenues of the media consumption curve "torso"? Without a promotional budget and/or curatorial guide, it seems neither camp could have much success. Still, this is an interesting look at "torso" models for content with inherent audiences (anime, bollywood, south korean drama, etc.). The Power of Torso TV (Why Media is Racing to the Middle)

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Mark Suster (@msuster), a 2x entrepreneur, now VC at GRP Partners. Read more about Suster on his Startup Advice blog: Both Sides of the Table

Chris Anderson wrote a really influential book some years ago called “The Long Tail” that shaped how many people think about emerging Internet markets. If you haven’t read it you should consider adding it to you library.

It was especially influential in my mind in thinking about media.

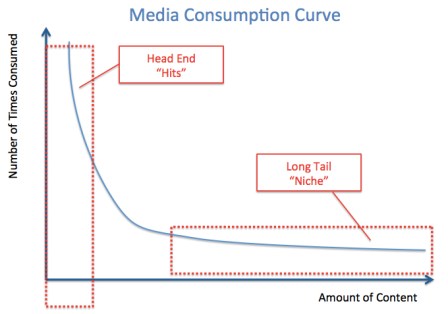

At the simplest level you can think about markets in terms of the number of times media is consumed and/or purchased by people plotted against the total number of content of that media type that is available.

At the left of the graph is the “head end” of the market, where the “hits” are produced for mass audiences. This was how companies who produced media became big before the Internet.

Why is that?

When you have limited distribution, the costs of distributing media are so prohibitive that only the largest of media producers (and distributors) are relevant.

The book profiles markets like those for books. When you had physical stores selling books, the bookseller would have to stock the shelves with those books most likely to sell so consumer choice was more limited. It was by definition a hits-driven business.

This changed with Amazon because you could stock books in warehouses and ship them when ordered greatly reducing the costs of housing books and thus you could stock a much greater variety.

Now as an author you can actually publish and be able to sell only a thousand books. Even a hundred. That couldn’t happen without the advent of lower cost production & distribution. And as we know the book industry is moving fully electronic with the advent of the Kindle making the costs of production & distribution nearly zero.

Think about music as another example.

In the early days of music you had to produce records, which was expensive. You had to promote them via music venues by playing across the country to get your albums purchased. And with the rise of radio you then had to get airplay on radios to promote your music (leading to payola).

If audiences liked your music then you had to sell them physically at Tower Records or similar. That was the only way. And you would promote your music through expensive and limited media channels (radio, who had a strangle hold on market) and retail shops (who could control placement and promotion).

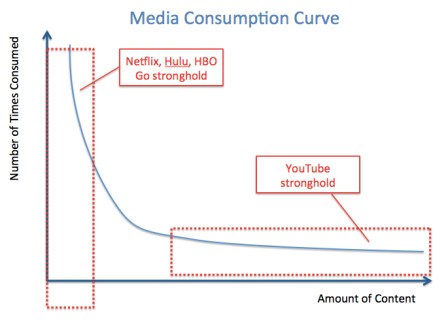

In the “head end” market you can make a lot of money if you’re a content producer. Mostly everybody else languishes. You also can make a lot of money if you’re a distributor to head-end markets, mostly these are monopolies, oligopolies or sometimes even mafia run businesses (for a great book on the emergence of these businesses read Lew Wasserman, The Last Mogul. Sadly, no Kindle edition).

In the “long tail” you can become enormously valuable if you’re a platform. Less so if you’re a content producer. It seems appealing at first since you can “ring the cash register quickly” and it feels good. But as every blogger, musician, novelist or YouTube emerging talent knows … it doesn’t add up to much unless you go big time.

TV was the same. You first had broadcast TV through local terrestrial broadcasting towers. The spectrum was so limited that as a child of the 1970′s we only got 4 TV stations. There were no physical forms to store the media – VHS, DVDs then DVRs have obviously changed this. Distribution strangleholds have dramatically decreased with cable & satellite (and now fiber) but distribution until recently has been very limited.

And then there’s film. It has been expensive to produce film on celluloid reels and then these had to physically be shipped to theaters (which were also, obviously, limited). When you think about “time windows” of film distribution you literally need to think about the fact that you would open a film in the US and later ship the physical reels to London then Europe to open overseas.

Physical limitations on both production AND distribution produced the hits driven business that many people associate with the media industry: Film, TV & Music.

We all know what happened with music when production costs went down (ProTools) and distribution costs went to zero (Napster). It had the effect of greatly reducing the industry size but also of allowing some less known artists to reach audiences that previously would be unthinkable due to cost constraints.

To some extent this lowering of production & distribution costs has been part of the YouTube phenomenon and more broadly of UGC (user-generated content) itself. YouTube has done a phenomenal job in aggregating audiences, which is why I have taken to calling YouTube the new Comcast and believe it will be a huge disruptor in the TV market .

To give you a sense of scale: 800 million people visit YouTube.com every month. 4 billion videos are watched daily. In 2011 YouTube had 1 trillion views, which is the equivalent of every human watching 140 videos. Put simply: YouTube OWNS the long tail. They own the audience and that is enormous asset to leverage, but more on that in a moment.

Netflix, Hulu & HBO Go are coming from the opposite direction – the Head End. Yes, it’s true that their deep libraries are virtual and therefore fit the long-tail properties. But their core asset (other than great tech & management) has been exclusive windowing of premium content that people want to consume.

They had to negotiate these rights with the major content owners – the studios. And this makes them definitionally more vulnerable than having control over a massive audience that turns up every month regardless of “hits.”

That is why Hulu has invested so much in building its Hulu Plus subscription service. With what is rumored to be around 2 million consumers paying $8 / month that is now a $200 million per year not including their ad revenue business.

Very smart people are running these online video businesses and they know that they need to diversify by either creating or sponsoring the development of new content. Hulu announced $500 million to fund new content and Netflix has, for example, resurrected the hit / cult show Arrested Development.

Interestingly Netflix plans to release the entire season all at once. Take that traditional time windows!

So to some extent I believe it will be a race in video will eventually be to the middle. The Torso. I know the big players still think of the next mega hit. But the fact that Netflix focused on Arrested Development tells me they are likely thinking more like me.

And I believe the torso is much more valuable than people perceive because it is growing rapidly with globalization and with the breakdown of physical distribution barriers.

Several years ago I became fascinated in the “torso” part of the media market.