Learning, Data, and Love

Forest Conner

One of the primary theses of my research is that people are not like films, people are like other people. As such, recommendation engines that try to base what you would like to watch on what you have already watched are inherently flawed. Even if this were the right starting point, the algorithms currently doing this work are likely to value the wrong things when comparing films. It is very possible to love Iron Man and hate Iron Man 2, but not according to these current systems.

So what should we be comparing? My belief is that people's behavior tells us what other people they are like, not what films they will like. I'm much more likely to watch a movie recommended by friends who share my tastes than by an advertisement, critic, or stranger. But if we are to accept this as the starting point, can we define people well enough to make the right match?

Well, that is certainly what I'm exploring in the film world, but some very smart man seems to have figured it out already in a not-so-different space: Love.

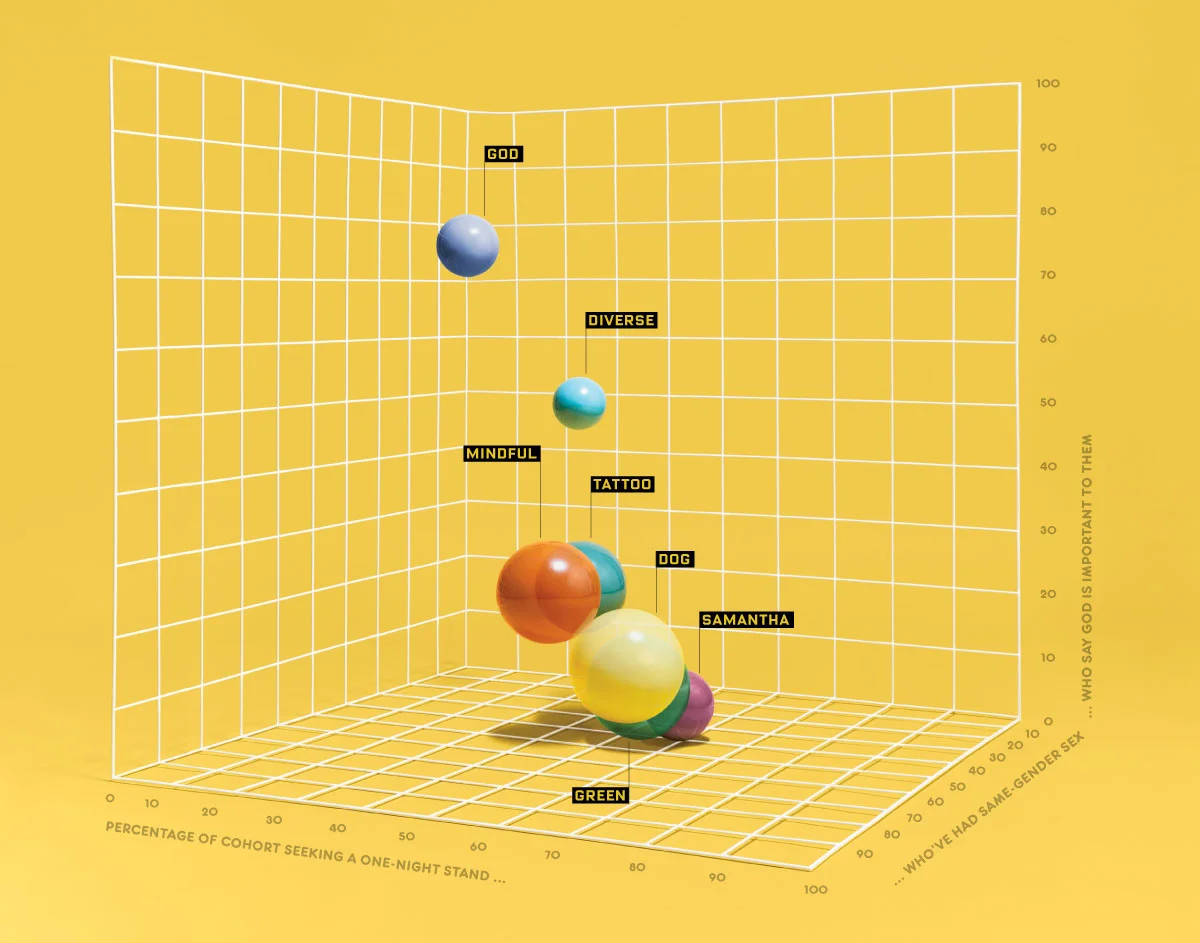

UCLA mathematician Chris McKinlay is profiled as doing just that in the Wired article How a Math Genius Hacked OkCupid to Find True Love. In short, he used data he collected by mining OkCupid to separate all female users into seven distinct cohorts. He could then look at the properties of these groups (age, religion, etc) and determine which fit the profile of someone he would want to date.

I certainly recommend reading the whole article (as the story of a mind who tries to find love by sleeping on a mattress in the cubicle of his office creates a compelling dichotomy,) but for the purposes of film marketing suffice it to say that this level of increase in marketing effectiveness is a virtual goldmine. McKinlay went from 100 high level matches out of 80,000 women (.1% effectiveness) to 10,000 high level matches (an insane 12.5% effectiveness rate!)

And it wasn't that he was lying to anyone. He just determined the right questions to answer that were the most relevant, and how important each of those questions were to the given cohort. Isn't this what marketing should be? Get the right message in front of the right people and your conversion rate soars.

At the risk of spoiling the article, I found this quote from McKinlay's now-fiancee to be the most illuminating.

“People are much more complicated than their profiles,” she says. “So the way we met was kind of superficial, but everything that happened after is not superficial at all. It’s been cultivated through a lot of work.”

The way we introduce people to movies for a marketing perspective is always going to be somewhat superficial. The key is to make sure that after that introduction has been made, there appears to be the right motivations behind it. This gives the audience a reason to trust you and your message, and creates a virtuous cycle.

While my research may not take us all the way to the promised land (and it certainly won't get anyone a date,) I think it begins to push the ways in which we evaluate and understand audiences and their preferences. Most importantly, experiments like this should show distributors, marketers, and even studios the benefits of exposing their data. After all, when do you think was the last time any of them hired someone with a PhD in mathematics?