Data and Metrics in Film

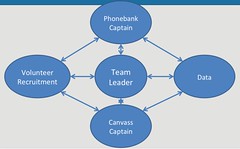

Michael Gottwald, Carl Kriss & Josh Penn

Hollywood is historically risk-averse; marketing-wise it will always want to use what has been shown to work before, even if it might not be the right fit for a certain film. They would rather attempt a tried-and-true set of tricks than take the time to do some research & development (like the Obama campaign) and get the numbers right. What if independent filmmakers used the same data collection and social media tools that have been proven to work for political campaigns? Would this help filmmakers engage their audiences the same way Votebuilder and My.BO helped the Obama campaign communicate with volunteers and voters – and without the bottom line costs of a major Hollywood marketing campaign? It is well known that the Obama machine was entirely built from data. In the BuzzFeed article “Messina: Obama Won On The Small Stuff,” Messina points out that, "Politics too much is about analogies and not about whether or not things work…You have to test every single thing, to challenge every assumption, and to make sure that everything we do is provable." The Obama campaign had an intricate data collection process that occurred both online and offline. Data was collected online everytime a new volunteer pledge their support on the website, through My.BO or gave a donation from an email blast. Organizers and volunteers also used a database called Votebuilder to collect data about supporters and undecided voters offline through canvassing and phone calls. This cycle of online and offline data collection played a key role in helping the Obama campaign adapt its strategy to the always shifting political climate. The more you know about who you are reaching, how you are reaching them and why they are interested the more you can figure out what outreach methods are working. Also, using offline canvassing and phone call methods to follow up with supporters who showed interest online added a personal touch that motivated many supporters to do more than just pledge to vote or donate money.

Could filmmakers engage more effectively with their audiences by using a data and metrics system similar to the Obama campaign? In the article, “Why we should build our own nations,” Ben Kempas observes, “It was during last year's election campaign of the pro-independence Scottish National Party that I first came across powerful software called NationBuilder, geared towards political use but flexible enough to be used for all sorts of campaigns, including outreach to those niche audiences of documentary films.” NationBuilder provides nonprofit, government and political organizations tools to create volunteer sign up pages and online feedback forms, similar to the U.S. digital agency Blue State Digital (used by the Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012.) As Kempas points out, filmmakers could also use these tools to interact and collect data from their fans. Even before a film is completed, filmmakers could engage with fans to grow their audience and gain insight into what methods would help distribute their film. Similar to the Obama campaign, filmmakers would then be able to shift resources and change their outreach strategy to best distribute their film.

However, the Obama campaign was able to collect its data through a massive team of organizers and volunteers that were doing non-stop voter contact -- to find out who in the voting populace (what places, and what demographics) were swaying their way, and to use their resources accordingly. These organizers and volunteers were able to be marshalled because they recognized and were energized by the urgency of electing the next president. In contrast, the cycle for a film’s distribution is often uncertain, much less nationally urgent, and, with independent films, certainly lacks the hefty "war chest" of resources that the campaign had. This leads us to ask, what can independent filmmakers do that is the equivalent of a voter contact program, to gage what kind of support it has amongst various communities of people? And when to start this: pre-production, production or after the film is made? What strategies could filmmakers use to keep their audience engaged before their film is completed? Does a film need to have a distribution plan before production, or like Four Eyed Monsters, can the filmmakers benefit from clever improvisation & properly pivot their campaign when the film’s process takes them in unexpected directions?

-Josh, Michael and Carl